important

The Data Stewardship Knowledgebase is under construction. Expect empty pages, warning signs, and hammers and nails left on the floor. It also might change drastically without notice.

Welcome

Welcome to the Data Stewardship Knowledgebase!

The Data Stewardship Knowledgebase, DSK for short, aims to be a handbook of useful resources for both current and future Data Stewards. You can navigate the DSK either with the sidebar, showing every section and chapter, or with the search function by clicking on the small magnifying lens on the top-left.

The handbook is not meant to be read top-to-bottom, but you could, if you wanted to.

Scope

The DSK covers a wide berth of topics. Some of them include:

- Define what data stewardship is, and provide insight on what meaningful data stewardship should look like in different contexts, with particular emphasis in the context of public research.

- Aggregate in an orderly way the resources found scattered on the internet, as data management can be a diffuse topic touching many aspects in many different contexts;

- Integrate information from other websites with additional context and, if needed, create new resources to fill in gaps from publicly available knowledge.

- Define lists of best practices and methods, as well as providing ways to find and define such methods, in a wide array of contexts;

- Provide practical guides and how-tos to deal with common or recurring problems when dealing with data stewardship and management in different contexts.

- Promote principles of meaningful data stewardship in many research contexts, and provide teaching material useful to promote such principles to a wide audience by Data Stewards and other people interested to do so.

- Promote the critical evaluation of the philosophy of science and the method of doing science of research groups and institutions through the collection of useful resources and teaching materials.

The DSK is structured in four broad categories of interest: Open Science, Computer Science Toolbox, Policy and Legal Issues and Stewarding the Data Lifetime. They are described below, so that you may be aware of the overarching structure of the DSK.

Open Science

The profession of Data Steward, and the concept of meaningful, useful data stewardship for the benefit of the community is the culmination of years of Open Science philosophy. This section aims to explore the aspects of Open Science, in particular in the context of data management. It covers topics such as:

- What Open Science is;

- Why is Open Science the right direction for researchers and research institutions to take;

- What could go wrong if Open Science is implemented badly;

- What do Data Stewards do in the context of Open Science;

- How to efficiently teach Open Science concepts to others;

- Why data and data stewardship matters so much for Open Science;

- Why a third party (like a researcher) might be interested in implementing Open Science and Data Stewardship policies;

Computer Science Toolbox

In the modern day, data is almost always manipulated digitally in some form. Even physical objects might be listed in a digital index, or scanned and digitalized altogether. For this reason, a Data Steward has to have some computer science knowlege and a toolbox of digital hammers and wrenches which are useful when dealing with digital data. This section covers topics such as:

- What digital data is;

- How digital data is encoded, transmitted and shared with others;

- What formats are available to save data in;

- What is metadata and in which formats are available to represent it;

- What data infrastructures are and how to manage them (as potential administrators);

- Technologies to manipulate, reshape, fuse and split data;

- Determination of costs related to data management (e.g. storage and computing power);

- Knowledge of relevant tools that can be used to obtain, reshape, reuse, manipulate and share data throughout a research project.

Policy and Legal issues

The administration of data, especially personal data, may be subject (or should be subjected) to laws. This section aims to aggregate such concepts and make a data steward both aware of them and capable of dealing with them. It covers topics such as:

- National and International privacy laws regarding personal data;

- Legal issues when reusing other’s code and data;

- Ethical concerns of releasing, reusing and otherwise manipulating data;

- Determining the ethical and legal risks related to handling specific types of data;

- How to give recognition when reusing a piece of data produced by others;

- Creation of effective Open Science policies and plans of action for groups and organizations;

- Fulfilling Open Science/Data Stewardship requirements for funding bodies that require them (i.e. DMPs);

- The soft skills required for effective management and administration of an organization interested in implementing data stewardship practices;

Stewarding the data lifetime

The most expansive and eterogeneous section, "Stewarding the data lifetime" deals with the philosophical, pratical and technical aspects of data stewardship, from the planning of data collection, to the manipulation of fresh data, to its potential deletion or archival, etc... This section is heavily context-specific: ideas that might apply to data in the context of biological science might not be relevant to Architectural studies, and vice-versa. This section covers many topics, and some examples include:

- How to plan data collection, even at large scales and with many data collection partners;

- Determining when, where and how to store newly created data;

- Defining and measuring data quality for specific data types in specific contexts;

- Designing and implementing data curation procedures, from collection to archival;

- Solving the discard problem and defining methods and formats of long to very-long term preservation of archive data;

- Determining the best methods of reusing published data to limit useless expenditures, with particular regards to ascertaining data quality and usefulness for the purpose.

Contributing

Thank you for wanting to contribute! Before contributing, please read the contributing guide in the Github repository of the project.

After you are familiar with how to contribute, you can use the edit icon in the top-right of each page to edit that page directly on GitHub and open a pull request with your change.

All contributions are treasured. You can find a list of all contributors in the contributors page. Thank you to all these wonderful people!

Emoji Key

Many links are tagged with emojis. Here's what they mean:

- Type of content:

- ➰ > A link to another page in the DSK.

- 💬 > Opinion piece, presentation, blog post or other content by an individual or organization.

- 📰 > News article, editoral or piece by a journalist.

- 🏢 > Official communication from an organization, oftentimes an institutional (i.e. Government-backed) organization.

- 🧑⚖️ > Text of a law or other binding document currently active in one or more countries. Associate the ❌ emoji if the law is no longer in effect.

- 📑 > Published research article or review in a canonical peer-reviewed journal, or similar (e.g. ongoing open peer review).

- 📄 > Preprint in a preprint server.

- 📃 > Poster or other vignette.

- 📕 > Book or long-form report.

- 💁 > Presentation to a meeting, conference, etc...

- 📝 > Official agreement, treatise or manifesto of purpose with no legally binding effects published by an organization or group of organizations.

- 🔨 > Tool, practical resource checklist or handbook.

- Format of content:

- The default format is a simple webpage (HTML), and has no associated emoji.

- 🔻 > PDF (

.pdf). - 🔸 > Presentation (e.g.

.pptx). - ▶️ > Video or other multimedia formats.

- Language:

- The default language is English, and has no associated emoji.

- 🇮🇹 > Italian.

- 🇫🇷 > French.

- 🇪🇸 > Spanish.

- Accessibility:

- The default accessibility is unrestricted (e.g. an Open Access paper), and has no associated emoji. Such resources should be freely perusable without any expense by the user (other than a computer, electricity and a web connection, obviously).

- 🔒 > This resource is paywalled, requires a login or is not publicly and freely available due to other reasons.

- 🔐 > This resource requires a login or registration in order to provide its services, but it is otherwise free to use or read.

- Content quality or fruibility:

- 🔰 > Easy to use, understand or in general a beginner-friendly resource.

- ⭐ > This resource is particularly important or fundamental for a topic.

- ❌ > Retracted, false or misleading information.

- Other:

- 🍪 > This website requires the usage of cookies.

- 📥 > This link immediately downloads a file to the user's computer.

- ⚫ > This link has been screened, but no other emoji tags apply.

Not all links are fully tagged. Please consider contributing if you find an error or an omission.

Using online resources to learn

The internet allows us to learn almost anything. There are a lot of resources for almost any topic you might wish to learn, each available to you at the touch of a button. The real skill isn't finding information, but it's knowing how to evaluate it, absorb it, and build genuine knowledge from it.

This is a weird page: it wishes to teach you how to use the DSK itself and resources you find on the internet, including this page, in order to truly learn and build skills you can use. In other words, it will give you the framework that expert learners use when approaching unfamiliar territory.

What are you learning?

Before diving into the learning process, pause. What exactly are you trying to learn? "I want to learn Python" is too vague. "I want to understand how to use nanopublications to share my results" is specific and actionable. Your learning purpose will guide every decision that follows.

Check your emotional state too. Are you frustrated and desperately searching for quick answers? Excited about a new topic? These feelings matter because they affect how critically you evaluate information. When you're angry or desperate, you're more likely to accept the first thing you find.

This resource, the DSK, helps you have a list of these specific topics to learn, and how they tie together in the overall big picture that is the Open Science and Research Data Management. It also gives you a curated list of resources which you can (and should!) use---hence the need for this page.

The Cardinal Rule

The most important thing this page is trying to teach you is the following:

If you do not understand a term, stop and find its meaning before moving on.

This is uncomfortable. It breaks your reading flow. It can turn a 10-minute article into a two-hour learning session. Do it anyway.

Here's why this matters: understanding is cumulative. If you don't grasp term A, you won't understand the sentence using term A. If you don't understand that sentence, you won't understand the paragraph. Before long, you're reading words without comprehending meaning—a complete waste of time.

The DSK tries to link to either the Wikipedia article for a specific term or similarly accessible resources which are beginner friendly. Such links are marked with the "beginner" symbol, 🔰: they are goo places to start looking for deeper understanding.

How to Handle Unknown Terms

Here's what to do when you encounter a term you don't understand:

- Consider the context: Consider what is the context in which the word is used in. What is the page talking about? Is the word composite (e.g. like "nano-publication"), and if so, can you decompose it?

- Search specifically: Don't just search the term alone. Search "what is [term] in [context]" to get relevant definitions. "Closure" means something different in psychology, mathematics, and programming. Having determined the context, as in the previous step, is essential here.

- Find multiple definitions: Technical terms especially benefit from seeing multiple explanations. Whenever possible, the DSK might link with multiple resources. Even if it doesn't, look for them if the first one you find isn't satisfactory to you.

- Verify your understanding: Can you explain it in your own words? Can you think of an example? If not, you don't really understand it yet.

This process feels slow at first, but it accelerates dramatically. The tenth unknown term takes less time to research than the first because you're building context. And critically, you're building actual understanding rather than surface-level familiarity.

It's important to keep notes on each term you don't understand, and even concepts you do understand. For example, you might use a notebook, a Word document or, even better, a platform specifically designed for these kinds of notes, like 🔨 obsidian or 🔨 :closed_lock_with_key: notion. Create a new note (or paragraph, or section) on each concept that you either did not know before, or that you find particularly important.

Asking good questions

It is often said that there are no bad questions. I disagree: it is extremely easy to find something you don't understand, be too lazy to try and understand it, and simply go online and ask someone (or even worse, an LLM) to explain it to you. You are putting the effort of learning on someone else, rather than on you: the pain of not understanding is a symptom of learning, similar to muscle pain is a symptom of going to the gym to get buff.

This is why it is very important to ask good questions. But, how can we do this?

The programming community has developed exceptional norms around self-teaching because code either works or it doesn't—there's no faking it. Therefore, if you don't understand something, it is painfully obvious to someone who has this understanding. To an expert eye, it is also easy to see if you actually put effort in trying to understand or you did not.

I show a summary of these rules here, but you can find many resources online which go in more depth:

Do your own problem-solving first

When something doesn't make sense or you hit a problem, your first instinct shouldn't be to ask for help. Instead, as yourself these questions:

- What exactly is the problem? Are you not understanding a specific term or concept? Are you not understanding how a certain thing is used? Did you lose the thread to the big picture that this concept fits in?

- Is your problem related to an error, for example while using a tool? If so, read the error. Do you understand what the machine is trying to tell you?

- Can you find a resource, for example looking online, that can be used to learn more about the problem, contextualise a new term, link the concept to the big picture?

- Can you go back, retrace your steps, and get to the concept you are having issues with again? Perhaps you simply lost or forgotten something along the way. Here, your notes are very useful.

- Has someone else already asked your question (or a very similar one)? Look online for similar questions which might help you. Forums, sites like Reddit or Stack exchange can be useful in this task.

If, and only if, you still cannot find an answer or explanation, feel free to ask a question: there are many people that want to and will gladly help you out.

How to ask for help

If you've genuinely exhausted your self-teaching options, then ask for help. But ask well:

- Give the people who are helping you the context of your question. What are you trying to accomplish? What's your background level? Where did you encounter this problem?

- Be as specific as possible. "I don't understand FAIR data" is too broad. "I understand that FAIR data is data that is more shareable, but I don't understand why this is important" is specific and answerable.

- What do you already know? What have you already tried? What resources have you consulted? This isn't just courtesy—it helps people give you better, more targeted answers.

- If relevant, provide minimal reproducible examples. Clean, well-formatted questions get better responses faster. Even a simple "hello" and a "thank you in advance" can go a long way to get people to

People who ask questions this way are respected in their communities. The ones who don't struggle to get responses and are seen as low-effort learners. Remember that most people who are helping you online are volunteers that devote their free time to answer questions.

Common Traps to Avoid

Here are a bunch of things to keep in mind as you learn from online resources and the DSK itself.

- The Collector's Fallacy

- Saving dozens of articles, bookmarking hundreds of tutorials, and creating elaborate reading lists feels productive. It isn't. You learn by engaging with material, not by hoarding it.

- It's better to pick one good resource and work through it completely before moving to the next.

- Tutorial Hell

- Endlessly following tutorials without building anything yourself creates an illusion of competence. You can follow along with guidance but can't apply the knowledge independently.

- Instead, after each tutorial, create something without following instructions. Rewrite what you learned in your own words. Start small if necessary, but create independently. After creating, look back at the source material and check if you got something wrong.

- Skipping fundamentals

- Advanced topics look more interesting than basics. But trying to learn advanced concepts without fundamental understanding is like trying to read before you know the alphabet. For instance, learning about advanced data structures without knowing anything about computer logic would be a waste of time.

- Be honest about your current level. Master fundamentals thoroughly even when they seem boring or you think you already know them: you'll thank yourself in the future.

Your Learning System

Effective self-teaching requires some structure. Here are some ideas on methods that may help you learn more effectively.

I suggest you keep a journal, a 🔰 bullet journal or 🔰 commonplace book in which you annotate with what material you engaged on any single day, what you did or did not understand, and what you plan to look into next. This allows you to first, pick back up where you left off immediately, and second, it allows you to notice patterns of difficulty on some kinds of topics, which suggest you need stronger fundamentals in that area.

I've already said to keep a notebook or digital collection of notes while you learn. These notes will be your own, personal, messy knowledgebase which you can tap into again and again while you work. Don't think about making it pretty for others - its main purpose is to be useful to you. Each minute spent on building your knowledgebase will pay off later (to a point, of course).

The methods that you can leverage to build such a resource are many. Here are just a couple:

- 🔒 Building a Second Brain - Tiago Forte, a way to sort your notes, based on the project-centric philosophy of "getting things done".

- 🔒 How to take smart notes - Sonke Arhens, which explains how to create and maintain a digital :star: zettlekasten system.

Tools used to create and store these notes are pen and paper, digital documents, or specific software like the aforementioned Obsidian or Notion.

Try to schedule regular study sessions. Sporadic learning is far less effective than consistent practice. Even 30 focused minutes daily outperforms occasional multi-hour sessions. Use your learning journal to schedule what to learn next, so you don't lose time when picking the subject back up.

Spaced repetition works! Revisit topics periodically to strengthen understanding and catch misconceptions. A common way to do this is to use flashcards, in which you write a question or concept on one side, and the answer, definition or explanation on the other. When reviewing, you look at the cards one the "question" side and try to answer, then check the back to see if you're correct. You can use these cards (or a subset of them) to review or "warm up" before starting your learning session. There are digital ways to do this, one such tool is ⭐ 🔨 ankiweb.

When learning a practical skill, like programming, building something yourself is extremely essential. Close the book or resource you are reading and test the tool you are learning how to use. Follow the tutorials but then try it out yourself, either doing the same thing or building something new. When learning how to program, for example, building simple projects like calculators and small games like tick-tac-toe may seem like a waste of time, but they are not: they are absolutely essential to learning as they make you face real-world problems that you will need to solve.

Basics

This chapter deals with the most basic definitions regarding Data Stewardship: who are data stewards? What do they do? Why are they important? What is the data that they steward?

All of these questions and more will be answered in this section.

Core competence of Data Stewards

Data stewardship and the position of Data Steward (DS) is relatively recent (~ 2017). Therefore, the "core competences" of DSs - what DSs do and what they know - are still being considered.

In this report, the FAIRsFAIR consortium has analised job offerings and other similar resources and generated a competence framework for DSs.

Here are reported such competences, with some modifications, from the above document.

note

Further work on this page will link core competences to relevant pages in the Data Stewardship knowledgebase.

Data Management

"Data Management" is an umbrella term covering all aspects of working with data, similar to "data handling". Many of these concepts also fall under the broad term "🔰 data curation".

- Develop and implement strategies for:

- Data collection;

- Data storage;

- Data preservation;

- Ensuring data is compliant with FAIR principles.

- Create Data Management Plans and Data governance policies, which are aligned with best practices in the field.

- Know and use relevant data and metadata data types and formats, as well as use and develop common standards for data and metadata.

- Be familiar, develop and use metadata management tools.

- Ensure recording of data provenance, including creation and manipulation, also through data publishing.

- Develop and implement strategies for long-term data archival, including:

- Develop data archival policies which complies with open science principles, open access policies and best practices for interoperability;

- Archival of metadata, with specific emphasis on data provenance;

- Policies for long term data accessibility and assurance of data integrity;

- Estimation of long-term data archival costs.

- Develop policies and methods to measure data quality and ensure compliance with community standards, also in coordination with data owners;

- Develop, implement and supervise policies on data protection, especially when sharing data, including:

- Compliance with data privacy laws such as the GDPR;

- Ethical issues;

- Address legal issues if necessary;

- Digital data security and integrity, referring to malicious data access, stealing and tampering;

- Collaborate with other Data Stewards and manage a team of Data Stewards;

- Coordinate data-related activities between departments and between departments and external collaborators in accordance with local and foreign data policies;

- Define domain-specific data management requirements, and supervise their development, also in collaboration with other departments.

- Coordinate and supervise data acquisition.

- Develop policies for the implementation of open science principles, including FAIR data;

- Define, develop and supervise required infrastructure for data management and archival;

- Provide tools, guidance and training to other experts that deal with data (e.g. researchers).

Data Engineering

"Data engineering" encompasses actual technologies that deal with data: collecting, analysing, transferring, storing and sharing it.

- Be familiar with modern computer science technologies, specifically to:

- Design and implement data analytics applications;

- Design and develop experiments, processes and infrastructure for data handling during the whole data lifecycle, including:

- Data collection;

- Data storage;

- Data cleaning (munging);

- Data analysis;

- Data visualization;

- Data archival;

- Develop and prototype specialised data handling procedures for specific needs.

- Develop and manage infrastructure for data handling and analysis, with emphasis on big data, data streaming and batch processing, while ensuring provenance and FAIRness.

- Develop, deploy and operate data infrastructure, including data storage, while following data management policies, with specific attention to the implementation of FAIR principles.

- Apply data security mechanisms throughout the data lifecycle, including designing and implementing data access policies for different stakeholders.

- Design, build and operate SQL and NoSQL databases, with particular attention to data models (structure), consistent metadata, data vocabularies and data accessibility.

- Develop and implement policies and methodologies for data reuse, interoperability and integration of local (i.e. of the organization) and external data.

Research methods and Project management

Data stewards need to work closely with researchers and other experts before, during and after research projects. It is therefore important to have competences in research management and more broadly project management. Some of this concepts might seem obvious and broad to people who have a research backgroud, but this might not be the case for people in all backgrounds.

- Create new knowledge (i.e. concepts, understandings, relationships and capabilities) through the scientific method based on scientific facts and data;

- Discover new approaches to achieve research goals, also through the re-usage of available (FAIR) data and software.

- Use available domain-related knowledge to generate novel sound hypotheses;

- Inspect and periodically audit the research process, with specific regards to quality, (i.e. integrity, soundness, and usefulness), openness and inclusivity.

- Design, develop and supervise data-driven projects, which include:

- Project planning;

- Experimental design, also in conjunction with domain experts such as Data Science, data infrastructure and other data stewards;

- Data collection;

- Data handling.

Domain-specific competences

Each research domain works with wildly different data types, formats and sources. This means that each domain requires a different sets of competences. This sections tries to outline in which contexts this domain-specific knowledge has to be taken into account.

- Use and adopt general Data Science methods to domain-specific issues, such as:

- Data types;

- Data presentations;

- Organizational roles and relations;

- Analyse, collect and assess data to achieve organizational goals, such as quality assurance of the organizational system;

- Identify and monitor performance indicators to identify and asses potential organizational challenges and needs. Specify data models, transparency policies and handling procedures for such performance indicators.

- Monitor and analyse indicators to identify current trends and potential future developments in local adoption of policies, methods, tools and other areas related to data management, FAIR implementation and open science. Ensure transparency of the process;

- Coordinate organization-level activities between different domains related to data management, provenance and analytics, with particular focus on data FAIRness throughout the data lifecycle.

What is data?

Defining what "Data" is is a hard task, as the concept is incredibly broad. Some of the most common definitions that people give when asked are:

- Everything that can be represented in bits.

- But what about a fossilized bone? Or a cave painting? Is an artefact not data? If not, what are museums for?

- Anything that can be used to extract Knowledge or insight.

- Is pure Logic-based derived thoughts data, then?

- Anything that a researcher uses to conduct its work.

- What work does a researcher do?

- What about non-human researchers? Do they count?

The EOSC Glossary used to define data as "reinterpretable digital representation of information in a formalized manner suitable for communication, interpretation or processing", which is also very bits-based (i.e. "digital representation"). As of today, 2024-08-03, the glossary no longer has any definition of "Data".

Sabina Leonelli, in her work "Scientific Research and Big Data", finds two possible definitions for what "Data" is. First, the representational definition for data: data is a representation, a "footprint" of the real world, captured in some form like a number, a sentence, etc...

In this view, data "captures" real features of the world and provides them with tangibility and the capability to be interpreted in order to generate Knowledge. Data objects are therefore immutable, and have well-defined, fixed, unchangeable context: that of the moment in which the data was recorded. In this sense, data is objective, and this very characteristics endows the resulting knowledge with epistemic value.

If data is an objective representation of reality, then it must be the case that there are correct and incorrect ways of interpreting it, just as there are correct and incorrect logical processes. However, the demarcation between what is a "correct" and what is an "incorrect" interpretation of data is unclear. Leonelli finds that the context in which the data is gathered and interpreted is essential to the very definition of what data is:

"[...] despite their epistemic value as ‘given’, data are clearly made. They are the results of complex processes of interaction between researchers and the world, which typically happen with the help of interfaces such as observational techniques, registration and measurement devices, and the re-scaling and manipulation of objects of inquiry for the purposes of making them amenable to investigation."

This led her to formulate a new definition for data, the so-called "relational view". This relational view arises from the statement quoted before: data is not given - it is made. The process of creating data is laden with human preconceptions and potential biases, as well as technical or practical constraints: it is "theory-laden". How can such a "theory-laden" object be found to be an objective representation of reality?

"How can data, understood as an intrinsically local, situated, idiosyncratic, theory-laden product of specific research conditions, serve as confirmation for universal truths about nature?"

The relational view defines Data as any product of research activities that can be used as evidence for scientific claims. In other words, the act of using something as evidence for a claim makes that something data.

This definition shifts the focus from the assumption that data is objective to the problem of supporting the usage of this or that piece of data to give credit to any given theory. This view of data more clearly allows the consideration of the need to scrutinize and explain the reason by which an object is considered to be data (evidence) for a specific theory or claim: how is this object used? how was this object obtained? who is using it to make the claim? what form does this object have, and how does it influence its interpretations? what manipulations has it undergone and how do these influence its fitness-of-purpose?

Leonelli also highlights data portability as an essential aspect of being data. Replicability is a core requirement for scientific statements, and similarly essential is the need of sharing one's evidence with a group of peers in order to support one's statements Data that is not portable, just as something that only one person has ever observed, has no meaning and therefore is not data.

This also means that the medium in which data is shared may affect its epistemic meaning:

"the physical characteristics of the medium significantly affect the ways in which data can be disseminated, and thus their usability as evidence. In other words, when data change medium, their scientific significance may also shift."

If this is the case, then Attribution of data creation might be ephemeral: if a person so profoundly edits the format that a dataset is in, or even combines it with others, is the new data completely new? Is authorship linked to the data, or its epistemic meaning?

An example: a scientist provides data on the migration of birds in different continents. The scientist defines five different continents: Europe, Asia, America, Africa and Oceania. To conform with the requirements of a deposition database, they are forced to change their definition of "continent" to more regions: East and West Europe, North and South America, etc... The data has not changed between the two formats, but arguably its epistemological meaning has.

Take away concepts

- Data is anything that is used to support a theory or claim.

- The context, the metadata, that lives around the data gives it shape and meaning, and is as essential as the data itself.

- The format which we use to share data has an effect on how the data may be used, and therefore its meaning.

- As the very definition of data relies on it being shared, sharing data with other individuals is essential.

Sources and Additional Reading Material

- Sabina Leonelli, 📑 "Scientific Research and Big Data", Plato Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2020

- Sabina Leonelli, 📑 "What Counts as Scientific Data? A Relational Framework", Philosophy of Science, 2016

Why is data stewardship useful?

In our current 🔰 Information Age, almost all :curly_loop: data is digital. Additionally, the amount of data is ever increasing. The simple fact that a lot of time, investment and research is being spent on the management and analysis of so-called big data is the perfect example of this.

Additionally, the rise of data-intensive 🔰 Artificial Intelligence (AI) models, which require massive amounts of curated data, placed a lot of focus on the way data is gathered, managed and ultimately used.

Data stewardship is a broad term which covers the way data---and in particular research data---is gathered, handled while being used, and ultimately shared to the public. In short, a data steward develops and implements data governance guidelines and policies for a certain institution. See the page on ➰ data steward competences to learn more. The DSK covers specifically the topic of research data management in the context of public research performing institutions, but these ideas can also apply to privately-owned companies.

Having good data governance policies, especially for a large institution, has deep, rippling benefits:

- The amount of data created and their quality is monitored and this monitoring data can be used for a variety of purposes, such as the overview of costs associated with data handling;

- Data loss and corruption is prevented via data protection and backup policies;

- The risk of forgetting or misinterpreting data created in the institution is minimized, thanks to the creation and maintenance of specific (meta)data standards and quality assurance procedures.

- Sharing data, especially following stringent requirements from founders, is first of all possible, and can be done quickly and easily;

- Risks of data duplication are minimized, as old, properly stewarded data can be reused in new applications again and again, avoiding repeated costs stemming from data acquisition;

- Sensitive data, such as that subjected to privacy policies such as the ➰ General Data Protection Regulation, is properly managed and protected, and correctly anonimized before being shared (if shared at all).

- Creation of in-house data storage and management solutions can give the institution better control over their assets, so that its output can be better appreciated and protected. Additionally, creation of these resources allows researches to fulfill the requirements set out by founders and national policies.

- For the public at large, robust (meta)data standards---particularly when implementing the FAIR principles---can aid in the creation of semantics-aware and copyright-compliant large-scale data orchestration tools, such as meta-analyses and AI tools.

For individual researches, the basics of data stewardship and administration can help in the management of day-to-day data, preventing data loss, confusion or errors during the analysis. Finally, data management policies are essential for the success of large-scale, multi-laboratory projects.

From the economical point of view, improper data stewardship causes a direct and indirect loss of more than 10 billion euro per year in Europe alone (see 🏢 this European union report) due to wasted researcher time and staunched economical growth.

For this point, it is often said that researchers lose about 80% of their time for data handling and management. This claim is repeated often: see, e.g. :speech_baloon: here, :speech_baloon: here, :speech_baloon: here, :speech_baloon: here or the book from Barend Mons "Data Stewardship for Open Science" (ISBN: 978-1-032-09570-7). Looking in depth at these sources, some of these claims may be overstated. A smaller, but still crucially very bad figure could realistically be lower, from 40% to 50%.

Barend Mons proposes that 5% of all project budgets should be devoted to hiring and paying data experts (and specifically data stewards) to reduce the friction for using data inside the project and re-use it outside of the project.

It is also important to remember that analysis processes, for data stewards, are simply another type of data - one what can be "executed". Therefore, data management policies and solutions also increase the quality, reproducibility and robustness of data analysis processes and therefore their results.

Finally, the conscious, purposeful management of data gives importance to it as the most fundamental scientific product, giving value and recognition to researchers which produce it and preventing fraud and other forms of academic misconduct.

Data stewardship can improve researcher efficiency, enhance or even enable their ability to collaborate, promote the transparency and robustness of results and has direct benefits, also in terms of economic opportunities and growth, to the institutions that implement it.

Computer Science toolbox

In the modern day, data is almost always manipulated digitally in some form. Even physical objects might be listed in a digital index, or scanned and digitalized altogether. For this reason, a Data Steward has to have some computer science knowlege and a toolbox of digital hammers and wrenches which are useful when dealing with digital data. This section covers topics such as:

- What digital data is;

- How digital data is encoded, transmitted and shared with others;

- What formats are available to save data in;

- What is metadata and in which formats are available to represent it;

- What data infrastructures are and how to manage them (as potential administrators);

- Technologies to manipulate, reshape, fuse and split data;

- Determination of costs related to data management (e.g. storage and computing power);

- Knowledge of relevant tools that can be used to obtain, reshape, reuse, manipulate and share data throughout a research project.

important

This section is heavily under construction.

Basics of computer science

- Files and filesystems

- Basics of the internet and shared computing

Programming languages

- What are programming languages?

- Python

Data Structures, serialization and storage

- Basic data structures and types

- Serialization and Deserialization

- Compression

AI and Machine Learning

- 🏢 📰 Use of generative AI in research guidelines by the European Research Area Forum

- 💬 Clearbox - AI Apocalypse, what to really worry about, garbage in, garbage out.

- 💬 Revelate - Bad data could ruin your AI dreams

Programming

Knowing the basics of 🔰 programming is essential for any data steward. Indeed, most modern data is captured and processed by computers. Additionally, the ➰ FAIR Principles are inherently enabling machines (and, therefore, humans) to access more data, more accurately, transparently and quickly.

Knowing the basics of computer programming also allows you to make sense of the main limitations inherently embedded in the way that computers process information. This, in turn, allows you to understand the reasons behind many Research Data Management (RDM) choices.

There are massive amounts of resources available online which can be used to learn programming even to high standards as a self-taught students. At the end of this page, you will not know programming, but you will be equipped with all the tools enabling you to learn it as quickly and efficiently as possible.

A data steward does not need advanced programming knowledge, such as that that a degree in computer science might net you, but, according to the ➰ data steward competence framework, a data steward should be able to:

- Develop and prototype specialised data handling procedures for specific needs.

- Develop and manage infrastructure for data handling and analysis, with emphasis on big data, data streaming and batch processing, while ensuring provenance and FAIRness.

- Develop, deploy and operate data infrastructure, including data storage, while following data management policies, with specific attention to the implementation of FAIR principles.

- Analyse, collect and assess data to achieve organizational goals, such as quality assurance of the organizational system;

All of these tasks (and more!) require or benefit heavily from some programming and computer science knowlege.

How computers process information

🔰 Computers are composed of several basic components:

- A 🔰 motherboard, which connects all other components together;

- A 🔰 central processing unit, or CPU, which performs basic arithmetic operations (such as sums, subtractions, and comparisons between numbers) at a very fast rate. A CPU's speed is measured in how many computations it can do in a second, in other words, its frequency. Modern CPUs can reach frequencies of more than 3 gigahertz (3 * 10^9), meaning 3 giga-computations per second.

- A computer is made up of many different types of 🔰 memory. Some, like Random Access Memory (or RAM) are very fast but require constant power to retain information. Others, like Hard Disks or the more modern Solid State Drives (SSDs) retain information even without power and thus for longer periods of time.

- To be useful, a computer requires a way to interface with human operators. This means it need to display its results (output) and accept inputs from humans. The devices that allow this kind of operations are called 🔰 Input/Output peripherals, or simply "Input/Output" or IO. Examples are screens, keyboards and mice.

While these are the most basic parts of a computer, it is important to underline that many more are possible, depending on the scale, size and complexity of the tasks placed on the computers themselves.

Computers process information via the CPU. The CPU may only perform basic operations: reading and writing to memory, adding values, subtracting them, comparing them, and a handful more. While the number of instructions are very limited, carefully designing complex series of instructions allows computers to perform a huge number of tasks. These series of instructions are called 🔰 programs.

CPUs are hard-wired in such a way in which the pattern of high and low voltages applies to specific wires in them causes the result of one of these basic structures to appear in another set out output pins. These differences in voltage are well described by binary numbers: either 0 for low voltage or 1 for high voltage.

CPUs can therefore only understand these patterns of 0s and 1s, causing them to perform one of their basic instructions. Writing these 0s and 1s is a difficult, almost impossible task, so methods of abstraction were developed in order to translate programs written in languages that humans can understand back to a series of instructions that a CPU might execute.

For example, summing two numbers, written out as basic CPU instructions, might look like this:

.code

main proc

mov ax, @data

mov ds, ax

mov ah, 09h

mov dx, offset message1

int 21h

mov ah, 1

int 21h

sub al, 30h

mov num1, al

mov ah, 09h

mov dx, offset message2

int 21h

mov ah, 1

int 21h

sub al, 30h

mov num2, al

add al, num1

mov result, al

mov ah, 0

aaa

add ah, 30h

add al, 30h

mov bx, ax

mov ah, 09h

mov dx, offset message3

int 21h

mov ah, 2

mov dl, bh

int 21h

mov ah, 2

mov dl, bl

int 21h

mov ah, 4ch

int 21h

main endp

end main

This is the language of the CPU, or machine code (actually, it ASCII, but the two are very similar). As you can see, this program (which, by they way, does not work) is almost impossible to decipher by anybody who is not an expert in computer science.

Abstraction programs have been designed to take some simpler language, such as 3 + 4 and translate it to the set of instruction above.

The two forms are identical in output, but wildly different in how easy they are to create.

These abstraction programs are called programming languages.

Programming languages

There are many different kinds of programming languages. Usually, they are subdivided into "high level" and "low level" languages: low level languages are closer to machine code, but provide programmers with a higher level of control on specifically what the CPU is doing at any one time, while high level languages are easier to use but restrict what the computer can do and, oftentimes, waste resources to provide programming simplicity.

When a computer is turned on, a small, hard-coded program is executed. This program is called a BIOS or, in modern computers, UEFI. The main task performed by the BIOS/UEFI system is to activate another program, called the Operating System, which in turn interfaces with all the systems attached on the motherboard, and allows to be a "mediator" between the hardware (e.g. the CPU or the monitor) and the programs that are executed on it.

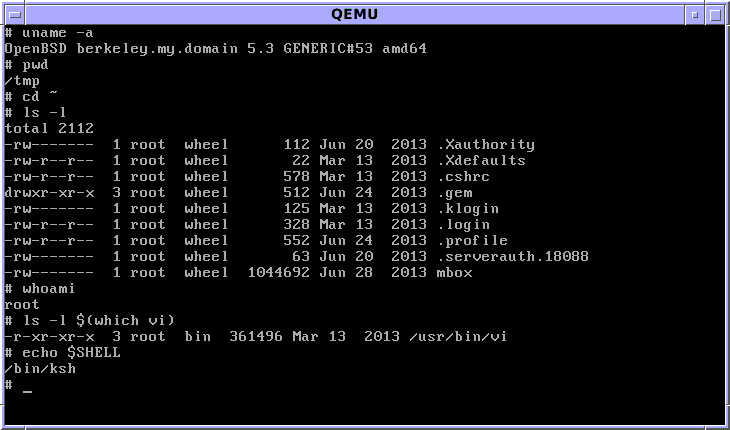

The main way to interact with the Operating System is another program called a 🔰 shell, which in turn allows exploring the memory on the computer, execute programs, and more. Shells accepts strings of text (typed with a keyboard) and output the results of the programs as text to the screen.

Examples of operating systems are Linux, Microsoft Windows, Mac OS and Android. Examples of shells are SH, BASH and ZSH. As BASH is the most popular and one of the oldest shells, most other shells follow in some way or another the conventions put forth by BASH.

The operating system might execute other programs when it starts, such as those showing a desktop, which allows manipulating visual programs, which can be more pleasing and easy to use than interacting with the shells.

The most basic programming language is the so-called shell scripting.

A shell script is simply a simple text file (.txt) with shell commands, one per each line.

Policy and legal issues

The administration of data, especially personal data, may be subject (or should be subjected) to laws. This section aims to aggregate such concepts and make a data steward both aware of them and capable of dealing with them. It covers topics such as:

- National and International privacy laws regarding personal data;

- Legal issues when reusing other’s code and data;

- Ethical concerns of releasing, reusing and otherwise manipulating data;

- Determining the ethical and legal risks related to handling specific types of data;

- How to give recognition when reusing a piece of data produced by others;

- Creation of effective Open Science policies and plans of action for groups and organizations;

- Fulfilling Open Science/Data Stewardship requirements for funding bodies that require them (i.e. DMPs);

- The soft skills required for effective management and administration of an organization interested in implementing data stewardship practices;

Intellectual Property Rights

- 🏢 🔻 Congressional research service report on generative artificial intelligence and intellectual property rights.

- 💬 🇮🇹 Simone Aliprandi, # Intelligenza artificiale e creazioni “sintetiche”: le intricate questioni di diritto d’autore

- 💬 🔒 🍪 Ben Lorica - The future of creativity

- 🏢 📰 Artificial Intelligence Act by the European Parliament

Stewarding the data lifetime

The most expansive and eterogeneous section, "Stewarding the data lifetime" deals with the philosophical, pratical and technical aspects of data stewardship, from the planning of data collection, to the manipulation of fresh data, to its potential deletion or archival, etc... This section is heavily context-specific: ideas that might apply to data in the context of biological science might not be relevant to Architectural studies, and vice-versa. This section covers many topics, and some examples include:

- How to plan data collection, even at large scales and with many data collection partners;

- Determining when, where and how to store newly created data;

- Defining and measuring data quality for specific data types in specific contexts;

- Designing and implementing data curation procedures, from collection to archival;

- Solving the discard problem and defining methods and formats of long to very-long term preservation of archive data;

- Determining the best methods of reusing published data to limit useless expenditures, with particular regards to ascertaining data quality and usefulness for the purpose.

Open Science

The profession of Data Steward, and the concept of meaningful, useful data stewardship for the benefit of the community is the culmination of years of Open Science philosophy. This section aims to explore the aspects of Open Science, in particular in the context of data management. It covers topics such as:

- What Open Science is;

- Why is Open Science the right direction for researchers and research institutions to take;

- What could go wrong if Open Science is implemented badly;

- What do Data Stewards do in the context of Open Science;

- How to efficiently teach Open Science concepts to others;

- Why data and data stewardship matters so much for Open Science;

- Why a third party (like a researcher) might be interested in implementing Open Science and Data Stewardship policies;

What is Open Science?

definition

Open science is a set of principles and practices that aim to make scientific research from all fields accessible to everyone for the benefits of scientists and society as a whole. Open science is about making sure not only that scientific knowledge is accessible but also that the production of that knowledge itself is inclusive, equitable and sustainable.

- 🏢 ⭐ UNESCO definition of Open Science

- UNESCO 🔻 🏢 Recommendations for Open Science

- 🏢 🔻 📥 ⭐ Strategic Research and Innovation Agenda: Critical success factors for Open Science in Europe.

- See sections 1.3 for the definition of Open Science and some historical facts.

- 🏢 🔻 📕 UNESCO - Open Science Outlook 1.

- This is a very long document (74 pages), on the status of Open Science in 2023, but has a section of "Key Messages" that summarize its message. These include the benefits of Open Science, how to achieve its goals, how it has grown and what it needs to grow further.

- 🏢 🔻 📥 Horizon Europe's application template with a section on Open Science practices

- Under the methodology section, the grant specifies that applicants should "Describe how appropriate open science practices are implemented as an integral part of the proposed methodology. Show how the choice of practices and their implementation are adapted to the nature of your work, in a way that will increase the chances of the project delivering on its objectives [e.g. 1 page]. If you believe that none of these practices are appropriate for your project, please provide a justification here."

- 💬 🇮🇹 Elena Giglia - Open Science è una necessità, non una noia burocratica

- An overview article about Open Science, scholarly publishing and the importance of making research accessible to everyone, also under the light of the covid-19 pandemic.

- 💬 💁 🔻 Dr. Jon Tennant - Open Science is just Good Science

- Tennant touches on what Open Science is, its benefits, and how to put it in practice.

History of Open Science

This section covers the history of Open Science, from its inception, to crucial events in its history, to the current day.

The Open Movement in Europe

Open Science has strong backing from the European Commission:

- 🏢 📕 European research area policy agenda Years 2022/2024

- Neelie Kroes, ex European Commissioner for Competition and Digital Agenda - 💬 ▶️ Let's make science Open

Open Science and Covid-19

The Covid-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of Open Science. This section includes resources that discuss how Open Science has helped in the fight against Covid-19 and how it went wrong in some cases.

- 🍪 📑 Open science approaches to COVID-19

- "In response [to COVID-19], researchers have adopted open science methods to begin to combat this disease via global collaborative efforts. We summarise here some of those initiatives, and have created an updateable list to which others may be added."

- 📑 OECD - Mobilizing Science in times of crisis

- What practices were used during the pandemic, how they worked, an the work needed in the future to make science more open and collaborative.

- 📕 🔻 The State of Open Data 2021

- "Open Data saves lives".

- A report on open data, including sections on the state of open data, its role in the life sciences, how open data can combat fraud, and how to engage researchers in its creation and use.

- 📰 Collaboration in the times of COVID

- 💬 All prints should be preprints

- An opinion piece on how the pandemic has shown the importance of preprints in scientific communication, as they immediately share knowledge with the community and the wide public. It also highlights some misconceptions about preprints.

- 💬 💁 ▶️ Robert Terry - Implications of the pandemic for publications

- 📰 Calling all coronavirus researchers: stay open

- A controversial editorial from Springer-Nature (which is a for-profit, closed publisher) that calls for researchers to share their data and findings openly during the pandemic.

- 💬 🍪 Don't lockdown research results

- 📰 STM makes open all coronavirus research for the duration of the outbreak.

- 💬 The purpose of publications in a pandemic and beyond

Open Science Organizations

This page collects some information about open science organizations together with a brief description, their motives and goals, and the services they offer.

Coalition S

cOAlition S is an organization built around "Plan S", a committment to make all articles written on publicly-funded research Open Access, effective immediately. You can read more on the cOAlition S about page and on :memo: Plan S.

- The 🔻 🏢 Coalition S preamble is the founding document of the coalition, with all considerations made when creating it plus its goals.

COARA

COARA, the Coalition for Advancing Research Assessment, is an organization striving to reform the methods for research assessment in accordance to ➰ Open Science principles.

In particular, they aim to find methods to reward all types of research outputs, not only publications and patents.

COARA is a coordinated group effort divided in 📰 COARA National Chapters and 📰 COARA Working groups. The COARA Website is the access point of all resources for the COARA initiative.

- Stakeholder may sign the "⭐ 📝 COARA - Full text agreement" in order to participate. It defines concrete goals, such as the creation of action plans.

- What are Action Plans and published COARA action plans on Zenodo

- 📝 🔻 COARA - See Annex 4 of the full text for useful practical tools and options to consider when dealing with research assessment: Annex 4 of the full text agreement

- A list of all signatories of the agreement is available in the signatories page of the COARA website

- Origins of COARA:

- The COARA funding document by the European commission: :office: :closed_book: European commission report - 2021 - Towards a reform of the research assessment system

- 🏢 📕 2021 - Outcomes of proceedings, on research evaluation;

- 🏢 📕 2018 - Commission Recommendations on access and preservation of scientific information

- 🏢 📕 2022 - Outcomes of proceedings, on research evaluation;

COARA and the force behind it has produced some changes:

- 📰 The ERC abandons the Impact Factor

- 📝 Making FAIReR assessments possible

- 🍪 📰 University of Uthrect rejects current university ranking standards

- 📰 Impact factor abandoned by Dutch university in hiring and promotion decisions

- 📰 Sorbona ditches WOS

- 📰 DORA case studies on the implementation of alternative metrics

- 🔨 Reformscape, an overview of ongoing changes and policies in research evaluation. Works a bit like a search engine.

Alternative metric sources, detached from canonical publishers and publishing in general are crucial for COARA. Here are a few tools and resources built for that regard:

- 🔨 Leiden Open Ranking, for the scientific performance of universities, publication-centric.

- 🔨 Open Alex, a non-profit organization that indexes publications. Similar to Elsevier's Scopus and Clarivate's Web of Science, Open Alex is an open, transparent replacement.

- 🔨 Open Citations provides a public, free index of citations (which papers cite which) for bibliometric and research purposes. It is chiefly useful for other applications that query its underlying knowledge graph (e.g. through SPARQL).

- 💬 The benefits of Open science are not inevitable: monitoring its development should be value-led

- 📕 ⭐ 🔻 OPUS - Reforming research assessment, on alternative indicators and metrics of researcher performance

- ⚫ PathOS and the :hammer: PathOS indicator handbook

- 📕 🏢 🔻 European commission - Indicator frameworks for fostering open knowledge practices in science and scholarship

Miscellaneous resources on the reform of research evaluation:

- ▶️ 💁 🇮🇹 Open Science Cafe' - Riforma della valutazione della ricerca

- 📄 What we talk about when we talk about research quality. A discussion on responsible research assessment and Open Science

- 📰 Revisiting the metric tide

- 🇮🇹 💬 Qualita' o formalita'?, an italian document on the European research assessment reform.

Scientific Communication

This section deals with scientific communication. In particular, it focuses on the role of publishers, how the publishing industry has changed over the years, and what new opportunities are available for researchers in the modern era.

- 🍪 💬 How to reclaim ownership of scholarly publishing

- Source of the quote "“I chose to study science because I wanted to publish in Nature,” said no undergraduate student ever."

- A piece about how the current publishing system is not working for researchers.

- 📝 SIMBA - Value of global scientific publishing

- Scientific publishing is a 12 billion dollar industry (in 2022).

- 🍪 📑 Rosendaal H. –Geurts P. Forces and functions in scientific communication:an analysis of their interplay, CRISP 1997

- An overview of the history of scientific communication, what functions it serves, and future prospects of its form in the digital age.

- 💬 Jean-Claude Guedon - Scholarly Communication and Scholarly Publishing

- How scholarly communication and scholarly publishing have diverged over the years, how scholarly publishing in the digital age currently is and how it could become.

- 📃 101 innovations in scholarly publishing

- 🍪 💬 Open science needs no martyrs

- An interview with Toma Susi, of the University of Vienna, touching on the need for reform in the publishing industry but that noone should pay for it in terms of career progression.

- 📑 🔻 Disrupting the subscription journal's business model for the necessary large-scale transformation to open access

- "This paper makes the strong, fact-based case for a large-scale transformation of the current corpus of scientific subscription journals to an open access business model."

- 📰 Costs, benefits of making all articles free to read, the stance of publishers.

- This is a controversial piece. On one hand, it provides an overview of open access, Plan S, and coalition S, but on the other hand it shows some of the arguments against open access. Unsure of what it should be tagged with.

- 💬 ACS and author's right retention, :newspaper: ACS news on Green Open Access and 💬 COAR's response of ACS news

- These articles discuss the American Chemical Society's new policy on Green Open Access, which requires authors to pay a fee to deposit their work in a repository.

- 💬 Jeff Pooley - Large Language Publishing, how LLMs are created on journal data.

The case of Elsevier

These resources discuss in particular the editor Elsevier, as a case-study.

- 💬 Publisher control of all scholarly infrastructure

- How publishing groups have started to control all aspects of research output: from planning research questions, to literature review, to data collection, to peer review, to publication, to dissemination.

- 📑 Jefferson Pooley - Surveillance Publishing

- "This essay develops the idea of surveillance publishing, with special attention to the example of Elsevier. A scholarly publisher can be defined as a surveillance publisher if it derives a substantial proportion of its revenue from prediction products, fueled by data extracted from researcher behavior."

- Navigating Risk in vendor data privacy practices, an analysis of Elsevier's ScienceDirect

- 📝 SPARC's 2021 Update

- SPARC is "a non-profit advocacy organization that supports systems for research and education that are open by default and equitable by design." (https://sparcopen.org/who-we-are/). This document "[...] suggests organizational changes in academic institutions to both (1) manage increasing strategic and ethical challenges and (2) deploy hammers and analyze data to better understand the needs and protect the interests of individuals and communities."

- 📝 📥 🔻 Direct PDF Link

- 📰 💬 Sci-hub, Elsevier and Wiley declare war on research communities in India

Alternatives to traditional publishing

- 📑 Principles of the self-journal of Science: bringing ethics and freedom to scientific publishing

- This article discusses the principles of the self-journal of Science, a new publishing model that aims to bring ethics and freedom to scientific publishing.

- 💬 Ten ways to find open access articles and 💬 alternative ways to access journal articles

Open Access

This section includes resources specifically about Open Access.

- 🏢 Berlin declaration on Open Access

- The founding document of the Open Access movement, it delineates the requirement to move away from paywalled content in the era of the internet towards Open Access. It defines what Open Access is, and how to support the transition to the open paradigm.

- 🍪 ScienceOpen - Open Access Survey results

- A survey of 60 researchers about Open Access.The low number of respondents makes the results not very reliable.

- Sampling strategy is also not clear. This may have been a convenience sample, on people who participated in a ScienceOpen event, making the results not generalizable.

- 📑 Shift academic culture through publication, an article discussing how exploitative publishers are a problem, especially discriminating poorer researchers.

- European Commission - 🏢 🔻 Study of scientific publishing in Europe (2024), on the state of scientific publishing in Europe, including publishing costs.

- 🇫🇷 🏢 Barometer of Open Science, data on the progressive shift to open publishing practices in France.

- DoaJ - 🔨 Open Access Journal repository

- Open Science Cafè - 🇮🇹 💁 Attività europee per l'open access

Sherpa helps authors decide where to publish, including services that compile what their rights are after publication. See 🔨 About Sherpa for an overview:

- 🔨 Sherpa Romeo: what are the archiving polices of different journal publishers? An author can go here to learn how to open up their articles, even when publishing in a closed-access journal.

- 🔨 Sherpa Juliet: what are the publishing requirements of funding agencies? Authors can check the publishing requirements based on who funds their research.

- 🔨 Sherpa Fact: combining data from Romeo and Juliet, it shows if journals are compliant with best publishing practices.

Some universities provide open access publishing services. An example is 🇮🇹 Sirio, for the University of Turin.

So called "hybrid journals" provide both open access and closed access articles. They are 🏢 generally regarded are bad for open access.

Preprints

A Preprint is an article ready to be sent for peer reivew. Such versions of the articles :bookmark_tab: usually differ little with their peer-reviewed counterparts, and are therefore a valid open alternative to reading regular articles.

The coronavirus pandemic required immediate action. Preprints were essential for this, as they provided immediate knowledge to the public.

- :bookmark_tab: Tracking changes between preprints and postprints during the coronavirus highlights how not much changes between preprint and published article during peer review.

Talking points

This section includes resources that discuss the importance of Open Science to a wider audience, including anectodes, examples, stories from researchers, comics, etc. They can be useful to introduce Open Science during talks, presentations and conferences.

- 🍪 📄 Valid reasons not to participate in open science practices

- There are no reasons. This is a joke paper.

- Dr. Glaucomflecken's videos on 🍪 ▶️ Academic Publishing and 🍪 ▶️ How to publish a manuscript

- These videos are a parody of the academic publishing system, highlighting some of its absurdities.

- 💬 Defence against the dark arts: a proposal for a new MSc course

Publishers can be very protective about the published data: it makes them a lot of money. See for instance, the case of Researchgate v publishers, Researchgate bows to publishers and Researchgate announcement on the topic.

Reproducibility Crisis

The reproducibility crisis we are experiencing in many research areas has highlighted the importance of Open Science. This section includes resources that discuss the reproducibility crisis and how Open Science can help alleviate it.

Contributors to the Data Stewardship Knowledgebase

Meaningful contributors to the project will be listed here.

List of maintainers

This is a list of currently active maintainers for the Data Stewardship Knowledgebase, in no particular order. They are responsible for reviewing and merging pull requests, as well as generally maintaining the repository and administering the public spaces of the project:

- MrHedmad - E-mail

luca.visentin(at)unito.it, Discord @MrHedmad.

All contributors

This is a list of all contributors to the project. Thanks to all these amazing people!